Winsor Fry

Winsor Fry spent his first years as a free man fighting for American liberty. But what did life in the new nation have in store for him?

Illustration by Dale Watson. In creating his unique art Watson used historical descriptions, images, and other resources to represent the figure or scene. If no description or image previously existed, Watson used historical research to represent what they might have looked like. Learn More

On the eve of Revolution, all thirteen rebelling colonies legally practiced slavery. Though there is no record of Winsor’s birth, it is likely that he was born enslaved. In 1773 prominent Rhode Islander Thomas Fry bequeathed “my Negro man named Windsor” to his youngest son Joseph, along with other property including several plots of land. Two years later however, Winsor joined the Continental Army as a free man.

Free people vs. slaves in the 13 colonies (1790)

- White

- Free Nonwhite

- Slave

Loading...

Fry took part in the Battles of , Harlem Heights, and .

In the first days of 1777 he fought at the (also called the Battle of the Assunpink Creek) and .

In December, 1777, General George Washington moved the Continental Army to their winter quarters at .

Winsor and many of his fellow soldiers fell ill as they endured the harsh winter.

Image: Winsor Fry at Valley Forge; Dale Watson

He survived, and went on to fight in the battles of and in 1778.

The legacy of Winsor Fry

Barbara Toney, a 6th-generation descendant of Winsor Fry, joined the Daughters of the American Revolution after her family learned of their heritage.

New burial monument: East Greenwich, RI

In 2019, new research allowed Winsor Fry’s decendants to gather at a private cemetery in East Greenwich, RI to dedicate a new monument to his memory.

Thayendanegea observes the failed British assault on Fort Carillon in 1758, and serves as a scout on the expedition against Fort Niagara.

Thayendanegea observes the failed British assault on Fort Carillon in 1758, and serves as a scout on the expedition against Fort Niagara. Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern colonies choses Thayendanegea as one of several Mohawks sent to attend Moor's Charity School in Connecticut

Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the northern colonies choses Thayendanegea as one of several Mohawks sent to attend Moor's Charity School in Connecticut George Washington purchases the slave that would come to be called Harry Washington

George Washington purchases the slave that would come to be called Harry Washington Button Gwinnett leaves England for Georgia.

Button Gwinnett leaves England for Georgia. Faith Trumbull marries Jedidiah Huntington.

Faith Trumbull marries Jedidiah Huntington. Button Gwinnett is elected to the Georgia General Assembly.

Button Gwinnett is elected to the Georgia General Assembly. Lucy Flucker marries Henry Knox.

Lucy Flucker marries Henry Knox. Thomas Brown establishes the settlement of Brownsborough near Augusta, Georgia.

Thomas Brown establishes the settlement of Brownsborough near Augusta, Georgia. Faith Trumbull Huntington visits her husband in Roxbury Massachusetts before the Battle of Bunker Hill.April 1775

Faith Trumbull Huntington visits her husband in Roxbury Massachusetts before the Battle of Bunker Hill.April 1775 Dearborn's militia unit marched to join the Patriot forces besieging Boston.May 1775

Dearborn's militia unit marched to join the Patriot forces besieging Boston.May 1775 Lucy and Henry Knox crossed over to the rebel camp.

Lucy and Henry Knox crossed over to the rebel camp. Thomas Brown joins a loyalist counter-association after the Georgia Provincial Congress votes to join the Continental Association.Aug 1775

Thomas Brown joins a loyalist counter-association after the Georgia Provincial Congress votes to join the Continental Association.Aug 1775 A patriot mob attacks and violently tortures loyalist Thomas Brown when he refuses to join their cause.Nov 1775

A patriot mob attacks and violently tortures loyalist Thomas Brown when he refuses to join their cause.Nov 1775 Virginia’s colonial governor Lord Dunmore issues a proclamation offering freedom to able-bodied men enslaved by rebellious colonistsNov 1775

Virginia’s colonial governor Lord Dunmore issues a proclamation offering freedom to able-bodied men enslaved by rebellious colonistsNov 1775 Brant travels to London and meets King George III and members of the British government. They promise to safeguard Indigenous lands in exchange for support against the colonists.Nov 1775

Brant travels to London and meets King George III and members of the British government. They promise to safeguard Indigenous lands in exchange for support against the colonists.Nov 1775 Faith Trumbull Huntington hangs herself in her bedroom.Dec 1775

Faith Trumbull Huntington hangs herself in her bedroom.Dec 1775 Christopher Greene is captured during the assault on Quebec

Christopher Greene is captured during the assault on Quebec Kirkwood received an officer's commission in the Delaware Regiment.

Kirkwood received an officer's commission in the Delaware Regiment. Button Gwinnett leaves Georgia for Philadelphia to represent the colony in the Second Continental Congress.

Button Gwinnett leaves Georgia for Philadelphia to represent the colony in the Second Continental Congress. Button Gwinnett signs the Declaration of Independence.Winter 1776

Button Gwinnett signs the Declaration of Independence.Winter 1776 Stephen Tainter joins his first Massachusetts militia unit

Stephen Tainter joins his first Massachusetts militia unit Bernardo de Gálvez becomes governor of Spanish-controlled Louisiana1777

Bernardo de Gálvez becomes governor of Spanish-controlled Louisiana1777 Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy arrives in Charleston, South Carolina.March 1777

Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy arrives in Charleston, South Carolina.March 1777 Dearborn received his parole and was exchanged.Spring 1777

Dearborn received his parole and was exchanged.Spring 1777 St. Leger begins to march east from Fort Oswego through the Oneida homeland.

St. Leger begins to march east from Fort Oswego through the Oneida homeland. Button Gwinnett meets Lachlan McIntosh for a duel. Gwinnett ultimately succumbs to his injuries.Summer '77

Button Gwinnett meets Lachlan McIntosh for a duel. Gwinnett ultimately succumbs to his injuries.Summer '77 Brant's volunteers join Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger's expedition.Aug 1777

Brant's volunteers join Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger's expedition.Aug 1777 Christopher Greene is released and promoted to colonel.Aug 1777

Christopher Greene is released and promoted to colonel.Aug 1777 The siege at Fort Stanwix leads Han Yerry Tewahangaraghkan and his warriors to join the Patriot relief effort.Aug 1777

The siege at Fort Stanwix leads Han Yerry Tewahangaraghkan and his warriors to join the Patriot relief effort.Aug 1777 Herkimer's reinforcements, including Han Yerry Tewahangaraghkan and his wife Tyonajanegan, are ambushed at Oriskany.Sep 1777

Herkimer's reinforcements, including Han Yerry Tewahangaraghkan and his wife Tyonajanegan, are ambushed at Oriskany.Sep 1777 Peggy Shippen is thrust into politics when British forces occupy Philadelphia after the battle of Brandywine.Oct 1777

Peggy Shippen is thrust into politics when British forces occupy Philadelphia after the battle of Brandywine.Oct 1777 Stephen Tainter is with General Gate's army when General Burgoyne surrenders at Saratoga.

Stephen Tainter is with General Gate's army when General Burgoyne surrenders at Saratoga. Bernardo de Gálvez gives refuge to American troops as they launch a raid into British-held Florida

Bernardo de Gálvez gives refuge to American troops as they launch a raid into British-held Florida Han Yerry Tewahangaraghkan and his warriors join George Washington's army at Valley Forge.May 1778

Han Yerry Tewahangaraghkan and his warriors join George Washington's army at Valley Forge.May 1778 Han Yerry Tewahangaraghkan and his warriors fight in the Battle of Barren Hill under the command of the Marquis de Lafayette.June 1778

Han Yerry Tewahangaraghkan and his warriors fight in the Battle of Barren Hill under the command of the Marquis de Lafayette.June 1778 The British Army retreats from Philadelphia, Peggy Shippen's hometown.1778

The British Army retreats from Philadelphia, Peggy Shippen's hometown.1778 Lucy bonded with Martha Washington at Valley Forge.Aug 1778

Lucy bonded with Martha Washington at Valley Forge.Aug 1778 Stephen Tainter witnesses the battle of Rhode Island, the first Franco-American operation of the war.Aug 1778

Stephen Tainter witnesses the battle of Rhode Island, the first Franco-American operation of the war.Aug 1778 The 1st Rhode Island Regiment participates in the Battle of Rhode Island.Dec 1778

The 1st Rhode Island Regiment participates in the Battle of Rhode Island.Dec 1778 British troops conquer Georgia leading Thomas Brown to raise the King's Rangers.

British troops conquer Georgia leading Thomas Brown to raise the King's Rangers.  Thayendanegea Brant received a British rank and salary as "Captain of the Northern Confederated Indians."1779

Thayendanegea Brant received a British rank and salary as "Captain of the Northern Confederated Indians."1779 Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy returns to France with Lafayette to encourage greater support for the American cause.Apr 1779

Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy returns to France with Lafayette to encourage greater support for the American cause.Apr 1779 Han Yerry Tewahangaraghkan is comissioned as a captain by CongressApr 1779

Han Yerry Tewahangaraghkan is comissioned as a captain by CongressApr 1779 Peggy Shippen marries American General Benedict Arnold.

Peggy Shippen marries American General Benedict Arnold. King Charles III declares war making de Gálvez responsible for managing the Spanish war effort in North America.Jul 1779

King Charles III declares war making de Gálvez responsible for managing the Spanish war effort in North America.Jul 1779 Sarah Osborn witnesses Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant and British loyalists engage patriot militia at the Battle of MinisinkOct 1779

Sarah Osborn witnesses Mohawk Chief Joseph Brant and British loyalists engage patriot militia at the Battle of MinisinkOct 1779 Thomas Brown's King's Rangers help defend Savannah from a patriot siege.

Thomas Brown's King's Rangers help defend Savannah from a patriot siege. Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy returns to America with Lafayette.May 1780

Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy returns to America with Lafayette.May 1780 The Culper Spy Ring secretly uncovers a message revealing that an American general is plotting with John André to help the British Army take control of West Point.Sep 1780

The Culper Spy Ring secretly uncovers a message revealing that an American general is plotting with John André to help the British Army take control of West Point.Sep 1780 Benedict Arnold meets John André and hands over maps and diagrams of West Point. André is caught two days later. Nov 1780

Benedict Arnold meets John André and hands over maps and diagrams of West Point. André is caught two days later. Nov 1780 A letter is discovered connecting Peggy Shippen to Benedict Arnold's plot.

A letter is discovered connecting Peggy Shippen to Benedict Arnold's plot. Kirkwood marched to the Cowpens, and on the 17th defeated Tarleton.Feb 1781

Kirkwood marched to the Cowpens, and on the 17th defeated Tarleton.Feb 1781 The 1st and 2nd Rhode Island Regiments are consolidated into a single regiment.May 1781

The 1st and 2nd Rhode Island Regiments are consolidated into a single regiment.May 1781 Spanish forces led by Bernardo de Gálvez take Pensacola after a two-month siege.May 1781

Spanish forces led by Bernardo de Gálvez take Pensacola after a two-month siege.May 1781 Christopher Greene is killed after a attack by De Lancey's Volunteers, perhaps especially aggressively due to his leadership of an integrated regiment.Jun 1781

Christopher Greene is killed after a attack by De Lancey's Volunteers, perhaps especially aggressively due to his leadership of an integrated regiment.Jun 1781 Thomas Brown and the King's Rangers surrender to patriot forces at the Siege of Augusta

Thomas Brown and the King's Rangers surrender to patriot forces at the Siege of Augusta Sarah Osborn watches the defeated British army marching out of Yorktown.Dec 1781

Sarah Osborn watches the defeated British army marching out of Yorktown.Dec 1781 Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy departs America for good, returning to France with Lafayette.

Michel Capitaine du Chesnoy departs America for good, returning to France with Lafayette. Harry Washington is evacuated to New York City as the remaining British troops organize their withdrawal

Harry Washington is evacuated to New York City as the remaining British troops organize their withdrawal Harry Washington leaves for a settlement in Nova Scotia (likely timeframe)

Harry Washington leaves for a settlement in Nova Scotia (likely timeframe) Bernardo de Gálvez dies of yellow fever.

Bernardo de Gálvez dies of yellow fever. Kirkwood joined the army at Fort Washington under Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair.

Kirkwood joined the army at Fort Washington under Maj. Gen. Arthur St. Clair.

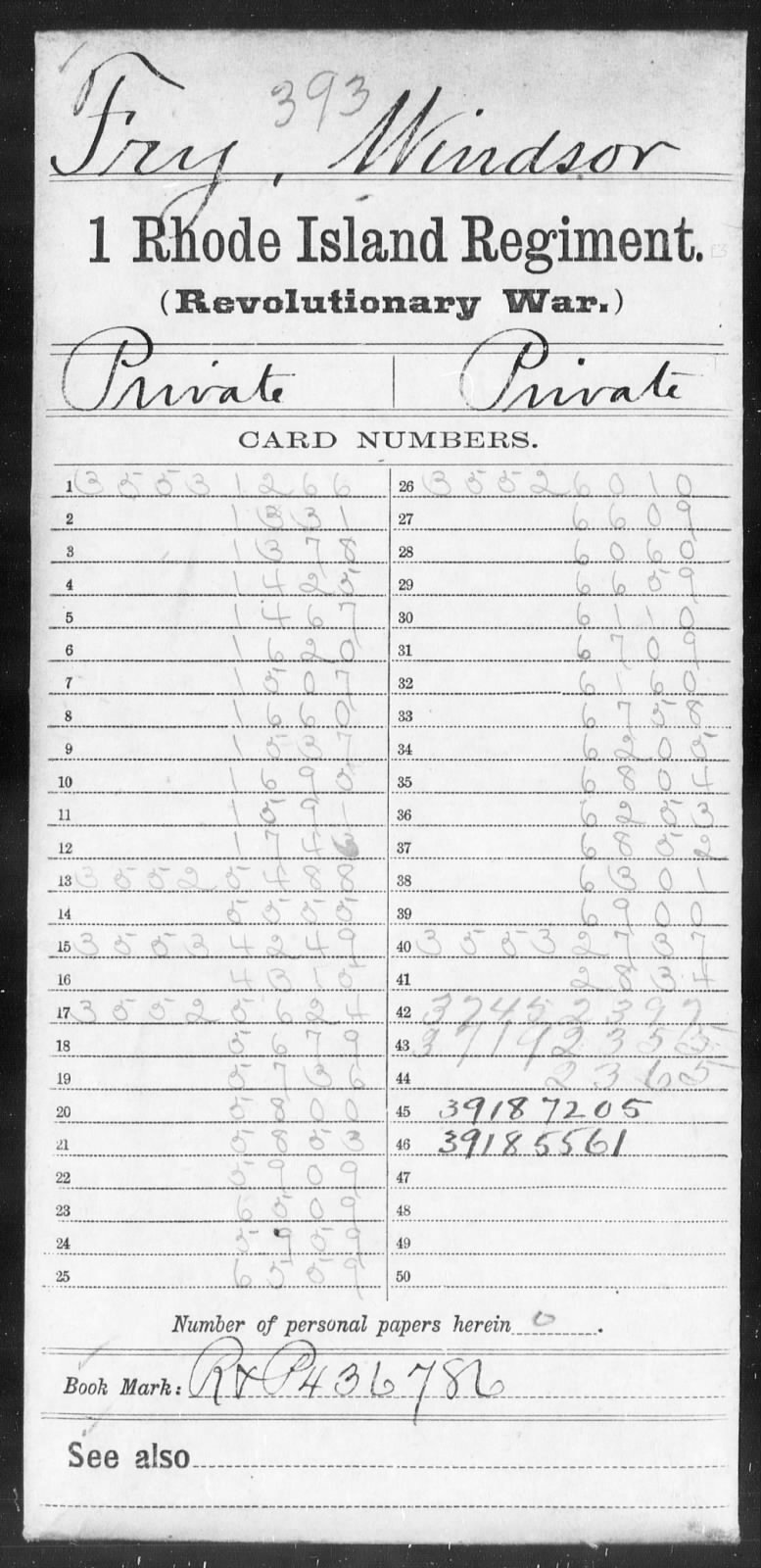

Compiled service record of Winsor Fry. Combined with other primary sources, these documents provide valuable information regarding the soldier which gives historians insight into their individual experiences. Credit: Fold3

This shovel head was excavated from the Yorktown battlefield. During his service at the siege, Winsor Fry might have used such tools to dig trenches and perform other manual labor.

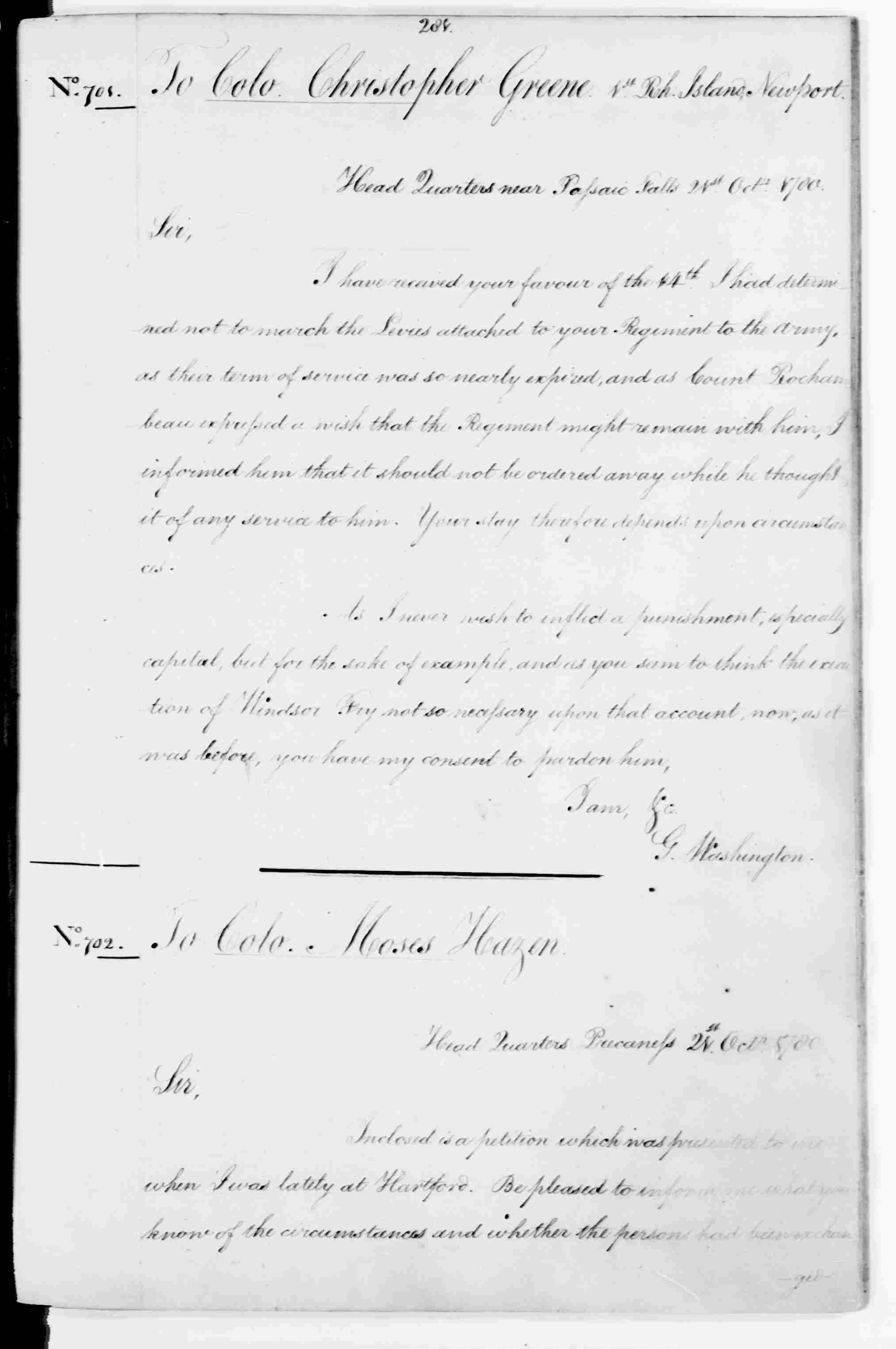

After considering Fry's case, Washington decided to issue a pardon.

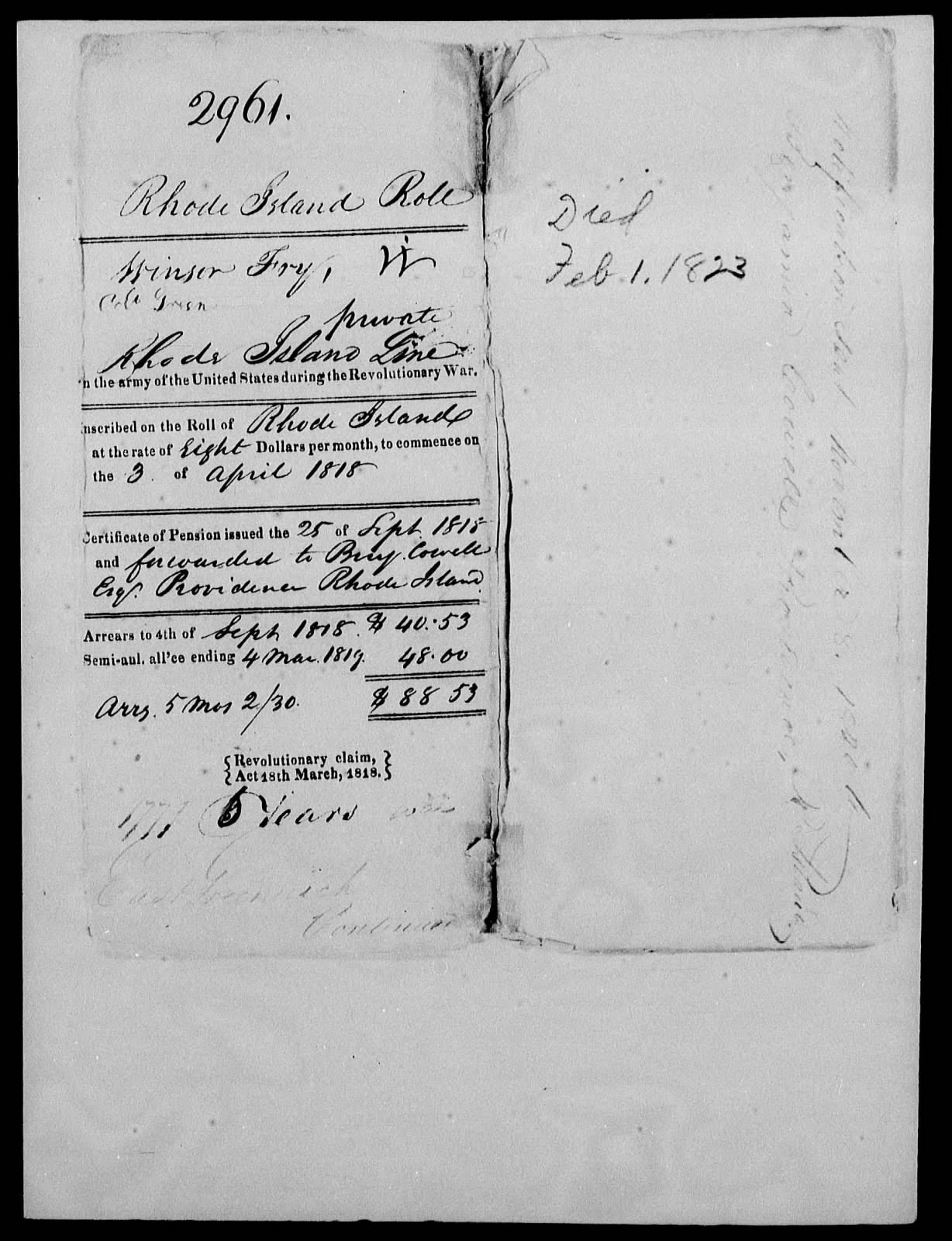

Winsor Fry applied for a pension in 1818. He would eventually receive a grant of around $8 a month in 1820. He never received a promised grant of land.

Image Credit: Ancestry.com. U.S., Revolutionary War Pension and Bounty-Land Warrant Application Files, 1800-1900 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010.

Bunker Hill

The battlefield today

While the city of Boston has swallowed up most of the Bunker Hill battlefield, visitors can still see the Battle of Bunker Hill monument, a 221-foot-tall obelisk commemorating the battle, and a statue of Colonel Williams Prescott, one of the ranking officers on the field for the New England militia during the battle, on the site where the battle took place.

Monmouth

The battlefield today

Monmouth Battlefield State Park maintains and interprets the battlefield where the Battle of Monmouth, also known as the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse, was fought on June 28, 1778. Three of the original seven farmhouses present during the battle are still standing today on the battlefield, including the Sutfin Farmhouse, the Rhea-Applegate House, and the Craig House. The 1,818-acre park has historic walking trails and a visitor center.

Lexington and Concord Battlefields

The battlefield today

Minute Man National Historic Park maintains and interprets multiple sites associated with the first day of fighting of the American Revolution, such as the Lexington and Concord Battlefields. In this first battle of the American Revolution, Massachusetts colonists defied British authority, outnumbered and outfought the Redcoats, and embarked on a lengthy war to earn their independence.

Germantown

The battlefield today

Germantown, a northwestern neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, was the site of the Battle of Germantown, fought on October 4, 1777, as part of the Philadelphia Campaign. Visitors can see a stone and bronze monument commemorating the battle erected by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in Vernon Park. There are also historical signs about the battle outside Cliveden, known as the Chew House, which was built in 1767 and witnessed the fighting.

Brandywine Battlefield

The battlefield today

The Brandywine Battlefield Historic Site maintains and interprets the battlefield where the Battle of Brandywine took place on September 11, 1777. While most of the battlefield has been overrun by suburban residential developments, visitors can still see the site of the Continental Army encampment, explore the area with a self-guided driving tour, and visit their site’s visitor center and museum.

Brooklyn Battlefield

The battlefield today

The Battle of Brooklyn, also known as the Battle of Long Island, was fought on August 27, 1776, and took place in what is now the neighborhood of Brooklyn. This is where efforts to fortify New York City from a British attack led to the Revolutionary War’s biggest battle and a crushing defeat for the Patriots. Currently, “The Old Stone House” stands where the Marylanders made their final effort to hold back the British, and the Dongan Oak Monument in Prospect Park lies where Continental troops cut down an enormous oak tree to slow the British advance.

Princeton Battlefield

The battlefield today

Princeton Battlefield State Park, just a mile southwest of Princeton University, maintains and interprets the scene of George Washington’s 1777 victory. The famous Mercer Oak, not far from where General Hugh Mercer fell during the battle, and Thomas Clarke House, built in 1772, both witnessed the fighting. An Ionic Collonade and stone patio on the property mark the grave of 21 British and 15 American soldiers killed in the battle. Together we have saved 24 acres at Princeton Battlefield.

Trenton Battlefield

The battlefield today

After crossing the Delaware River in a treacherous storm, General George Washington’s army defeated a garrison of Hessian mercenaries at Trenton. The victory set the stage for another success at Princeton a week later and boosted the morale of the American troops.

White Plains

The battlefield today

The Battle of White Plains fought on October 28, 1776, took place north of New York City in current-day White Plains, New York. George Washington had moved to this fortified position after the American defeats at the Battles of Long Island and Harlem Heights. However, American forces couldn’t hold the position, and Washington was soon forced to abandon New York and retreat across New Jersey.

Fort Stanwix

The battlefield today

Fort Stanwix National Monument is a reconstructed bastion fort initially constructed in 1758 during the French and Indian War located in present-day Rome, New York. The site has three short nature trails and a visitor center discussing Fort Stanwix's role in eighteenth-century history.

The fort played a critical role in the Saratoga campaign of 1777. It was a target for British General John Burgoyne, who sent brevet Brigadier General Barry St. Leger to capture it. Opposing St. Leger was the 3rd New York Regiment under Colonel Peter Gansevoort.

Oriskany Battlefield

The battlefield today

The Battle of Oriskany was part of British operations in the Hudson Valley. The British, under the overall command of General John Burgoyne, planned to move south from Quebec and capture Fort Ticonderoga and Albany. British General William Howe was to march north from New York and rendezvous with Burgoyne at Albany, effectively severing New England from the rest of the colonies.

Saratoga Battlefield

The battlefield today

Saratoga National Historical Park maintains and interprets the battlefield where the Battles of Saratoga took place from September to October 1777. While exploring the park, visitors can see the famous Boot Monument, which commemorated Benedict Arnold’s role in the battle and is the only war memorial in the U.S. that does not bear the name of its honoree; the Saratoga Battle Monument; a visitor center, which runs a 20-min orientation film; and walking trails.

Yorktown Battlefield

The battlefield today

The Colonial National Historical Park maintains and interprets American history from the first English settlements in the Colony of Virginia to the battlefields of Yorktown, where the British army surrendered to the Continental Army in October 1781. Though established to commemorate the colonial era, this park also was the site of the 1862 Battle of Yorktown fought during Gen. George B. McClellan’s Peninsula campaign. Together we have saved 49 acres of land in the area.

Great Bridge Battlefield

The battlefield today

The Great Bridge Battlefield, run by the Great Bridge Battlefield & Waterways History Foundation, commemorates the first American victory of the Revolutionary War at the Battle of Great Bridge on December 9, 1775. The Park is home to a historic interpretive pathway, an outdoor amphitheater, a recreation of the causeway from 1775, and a family picnic area.

Port Royal Island Battlefield

The battlefield today

Mostly overrun by residential and commercial development around nearby Beaufort, South Carolina, a small parcel of wooded land on the west side of U.S. Route 21 marks the location of the skirmish on Port Royal Island, fought on February 3, 1779. The battlefield is located near Gray's Hill, the highest point of land on the island, about 6 miles north of downtown Beaufort, and the site is marked by a nearby historic marker.

Savannah Battlefield

The battlefield today

Located across the street from the Savanna History Museum, the Battlefield Memorial Park commemorates the Siege of Savannah from September to October 1779 on the city of Savannah by the Patriot forces and, more specifically, the Battle of Savannah on October 9, 1779. Visitors can explore the site and take guided tours to learn more about the Southern Campaign and Savannah’s role in the American Revolution.

Camden Battlefield

The battlefield today

The Battle of Camden fought on August 16, 1780, was one of several devastating defeats suffered by the Americans in the early stages of the British military offensive in the South. This defeat cleared South Carolina of organized American resistance and opened the way for General Charles Lord Cornwallis to invade North Carolina.

Charleston

The battlefield today

In downtown Charleston, South Carolina, visitors can visit Marion Square and read a historical marker describing the 1780 Siege of Charleston, which ended in British forces successfully taking the city and gaining access to Charleston Harbor. Nearby, visitors can also see Fort Moultrie, which the American forces unsuccessfully used to defend the city from British attack during the siege.

Cowpens Battlefield

The battlefield today

The Cowpens National Battlefield in South Carolina commemorates Daniel Morgan's victory over Banastre Tarleton on January 17, 1781. At this 845-acre site, which served as a pasturing ground at the time of the Revolutionary War, there is a visitor center featuring a museum, a walking tour of the battlefield, and a reconstructed log cabin of Robert Scruggs, a farmer who lived on the land.

Eutaw Springs Battlefield

The battlefield today

Located near modern-day Eutawville, South Carolina, the Eutaw Springs Battlefield preserves a portion of the site of the last Revolutionary War battle in the Carolinas fought on September 8, 1781. On the site, visitors can read historical signs about the battle and visit the grave of British officer Major John Marjoribanks.

Guilford Courthouse Battlefield

The battlefield today

Located in Greensboro, North Carolina, Guilford Courthouse National Military Park preserves the largest battle of the Southern Campaign. Park visitors may tour the museum, take a guided tour of the battlefield, or tour the colonial home of Joseph and Hannah Hoskins on the site.

Hobkirk Hill Battlefield

The battlefield today

Near Camden, South Carolina, British forces attacked a small force under Nathanael Greene stationed on Hobkirk Hill on April 25, 1781. After a brief skirmish, the American troops retreated. A battlefield marker detailing the battle is located at Broad Street and Greene Street, two miles north of downtown Camden.

Ninety Six Battlefield

The battlefield today

The Ninety Six National Historic Site commemorates the Battle of Ninety Six, one of the first battles fought outside New England in the South Carolina backcountry during the Revolutionary War. The site has preserved the Star Fort, an 18th-century earthen fortification utilized by Nathanael Greene and his Patriot troops to defend the small town of Ninety Six.

Pensacola

The battlefield today

Visitors can learn more about the siege of Pensacola at Fort George Park in Pensacola, Florida. While the original 1778 fort no longer exists, the park marks its original location and has a partial reconstruction of the structure. In addition, visitors can read historical markers talking about the fort, the siege, and Florida’s role in the Revolutionary War at the site.

Bennington Battlefield

The battlefield today

Bennington Battlefield State Historic Site maintains and interprets the battlefield where the Battle of Bennington took place on August 16, 1777. On the 276 acres of preserved battlefield land, visitors can learn more about the battle at the visitor center or explore numerous walking trails. In the nearby historic village of Bennington, visitors can also see the 306-foot-high stone obelisk commemorating those that fought in the battle.

Rhode Island Battlefield

The battlefield today

Declared a National Historic Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Heritage Park in Portsmouth, Rhode Island, is the site of the Battle of Rhode Island that took place on August 29, 1778. Today the site has an interpretive sign explaining the history of the battle, and visitors can see a memorial to Rhode Islanders who lost their lives during the conflict in nearby Patriot’s Park.

Newtown Battlefield

The battlefield today

Newtown Battlefield State Park was the site of the Battle of Newton that signaled the end of the Sullivan Campaign, the drive ordered by George Washington to remove the mostly pro-British Iroquois nations from the New York frontier and end the threat they posed. Located along the eastern bank of the Chemung River in western New York, visitors can still visit the site today and explore the battlefield on walking trails.

Sentry Box

Brothers-in-arms and brothers-in-law George Weedon and Hugh Mercer purchased land on what is now Caroline Street in Fredericksburg, VA. After the American Revolution, Weedon built what is known today as the “Sentry Box,” a large two-story building that drew from Federal, Georgian, Greek Revival, and Colonial Revival architecture on the property. During the Civil War, the house witnessed the Battle of Fredericksburg in late 1862.

Star Fort

Built by Loyalist soldiers and slaves from nearby plantations, the Star Fort was constructed between December 1780 and early 1781 outside of Ninety Six, South Carolina. Because of the terrain outside the town, Loyalist engineer Lt. Henry Haldane thought the eight-point star would be better suited to defend the area instead of a more traditional square fort. From May to June of 1781, Patriot General Nathanael Greene besieged the vital South Carolina post of Ninety Six; however, he was unable to capture the fort or the garrison.

John Trumbull Birthplace

The Trumbull family home in Lebanon, Connecticut, was built in 1735 by Joseph Trumbull as a wedding present for his son Jonathan and his wife, Faith Robinson. Jonathan became the governor of the Connecticut Colony in 1769 and then the first Governor of the State of Connecticut in 1776. Throughout the American Revolution, the home served as a center for Patriot activity in the area.

In 1743, Faith Trumbull Huntington was born in the home and lived there until she moved to Norwich, Connecticut, with her husband Jedidiah Huntington in September 1767.

Fort Dearborn

Fort Dearborn was built in 1803 along the Chicago River on land now in Chicago, Illinois. It was named after Revolutionary War veteran and the U.S. Secretary of War Henry Dearborn, who commissioned the fort's construction. The original fort was burned in August 1814 during the Battle of Fort Dearborn, and it was rebuilt the following year and manned intermittently until it was destroyed by fire in 1857.

Today, the fort outline is marked by plaques and information signs about the fort's history.

Great Dismal Swamp

Located in the Coastal Plain region of southeastern Virginia and North Carolina, between Norfolk, Virginia, and Elizabeth City, North Carolina, the Great Dismal Swamp is protected by the Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge, created in 1974. This site was the refuge location for the Great Dismal Swamp Maroons, who were comprised of African Americans escaping slavery and Native Americans who were escaping colonial expansion. It was also the site of several American Revolution skirmishes.

Montpelier

Henry Knox Estate

After retiring as Secretary of War in 1795, Henry Knox and his family moved to modern-day Thomaston, Maine, on land his wife Lucy had inherited and into the home they built the year prior named Montpelier. Henry and Lucy lived on the estate until his death in 1806 and her death in 1824. The estate stayed in the family until 1871 when the home was demolished to make room for a local railroad line. Today, visitors can see a 1929 re-creation of the house and learn more about Henry and Lucy Knox in the Knox Museum on the site.

Fort Recovery

Purposely built on the site of Arthur St. Clair’s defeat in 1791, General “Mad” Anthony Wayne oversaw the construction of Fort Recovery along the Wabash River, within two miles of the modern Ohio and Indiana border. Built between 1793 and 1794, the fort was used as a staging ground for advances into the northwest territory. It was eventually used as a reference point to establish the border between Native American and United States territories.

Today, a replica of part of the fort is on the site in addition to the Fort Recovery State Memorial and the Fort Recovery State Museum. The memorial honors those that were killed under the commands of Arthur St. Clair and Anthony Wayne.

Fort Washington

Construction started for Fort Washington in the summer of 1789 by General Josiah Harmar in modern-day downtown Cincinnati, Ohio, near the Ohio River. Named in honor of President George Washington, the fort was used as a staging ground for settlers, troops, and supplies during the settlement of the Northwest Territory. In addition, it served as a staging ground for three Indian campaigns, Harmar’s Campaign in 1790, St. Clair’s Campaign in 1791, and "Mad” Anthony Wayne’s Campaign in 1793-1794.

By 1803, the fort had fallen into disrepair, and troops were moved across the Ohio River to the larger Newport Barracks in Newport, Kentucky. By 1806, the land where Fort Washington stood was divided into lots and sold.

Fort Barton

Added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1973, the Fort Barton site still has the earthwork remains of Fort Barton, constructed in 1777, used as a defensive post overlooking the ferry crossing between Tiverton and Aquidneck Island during the American Revolution. This ferry was used as a launching position for American forces during the Battle of Rhode Island in August 1778. The fort was named after Lt. Col. William Barton, who captured British General Richard Prescott during a midnight raid at Prescott Farm.

New Windsor Cantonment State Historic Site

The New Windsor Cantonment State Historic Site was the site of the Continental Army’s last military encampment from June 1782 until October 1783. While the Siege of Yorktown had ended with an American victory and peace talks started between the two nations, George Washington was worried about British resistance in New York City. To discourage fighting, he stationed his troops near Newburgh, New York, until the British officially withdrew from the city. In addition, this site is where Washington dealt with the Newburgh Conspiracy, a conspiracy among senior Continental Army officers in 1783 against the Confederation Congress to receive their pensions and back pay for serving in the Revolutionary War.

Fort Mercer

Built in 1777 by Thaddeus Kosciuszko on the Delaware River in Red Bank, New Jersey, Fort Mercer was used in tandem with Fort Mifflin to block the approach to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The fort was named after Brigadier General Hugh Mercer, who had died earlier that year at the Battle of Princeton, and was the site of the Battle of Red Bank, fought on October 22, 1777, where American forces successfully defended the fortifications from the British. However, the fort was abandoned after Fort Mifflin was lost in November 1777 and fell under British control until June 1778. When the British evacuated the fort, the Americans once again occupied the fort until the war moved south in 1781.

Fortress West Point

Fortress West Point was a series of fortifications arraigned on the west bank of the Hudson River and Constitution Island. Spanning the river between the two locations was The Great Chain, a chain supported by log rafts stretched across the river to impede British movement north of West Point.

On the heights of the west bank stood Fort Arnold, the largest at Fortress West Point. Named after Benedict Arnold, who oversaw the fortifications at West Point, it was renamed Fort Clinton in honor of James Clinton after Arnold defected to the British. Fort Putnam protected the landward side of Fort Arnold, a stone fortification that included three interior casemates, two bomb proofs, and a provision magazine. Across the river on Constitution Island was Fort Constitution, which was only partially completed in 1776, with efforts and materiel being diverted to Forts Montgomery and Clinton. When Montgomery and Clinton fell in October 1777, Fort Constitution was also captured and destroyed by the British. In 1778, the fort was partially rebuilt to protect the eastern end of The Great Chain.

On July 4, 1802, Fortress West Point ended its defense of the Hudson and officially became the United States Military Academy.

Morristown National Historical Park

Morristown National Historical Park commemorates the Continental Army’s second winter encampment from December 1779 to June 1780, one of the coldest winters in North America on record. Previously, Washington had selected Morristown for the army’s camp in the winter of 1776-1777, following the Patriot victories at Trenton and Princeton.

Visitors can see Jockey Hollow, the Ford Mansion, Fort Nonsense, and the New Jersey Brigade Encampment site in the park, in addition to a museum and library collection that showcases items related to the encampment and George Washington. This site was also the first National Historical Park when it was established in March 1933 in the last days of Herbert Hoover’s presidency.

Washington's Headquarters (Isaac Potts House)

General George Washington rented a three-story stone house to serve as his headquarters during the Continental Army’s winter encampment at Valley Forge from 1777-1778. Built in the 1750s by the Potts family, Deborah Hewes rented the house from her relative Isaac Potts, who, in turn, leased the entire house, with furnishings, to Washington. Today, Washington’s Headquarters, sometimes known as the Isaac Potts House, is open for visitation in Valley Forge National Historical Park and reconstructed to look like what it looked like during the winter of 1777-1778.

Fort Clinton

Built between 1778 and 1780 near West Point, New York, Fort Clinton was initially known as Fort Arnold in honor of Benedict Arnold, who commanded the fortifications at West Post. Once he defected to the British Army, the fort was renamed Fort Clinton in honor of General James Clinton. The fort overlooked and protected the Hudson River, and the Great Chain, a chain supported by log rafts stretched across the river to impede British movement north of West Point. After the American Revolution, the fort fell into disarray and was eventually demolished to make room for the expansion of the United States Military Academy at West Point.

Valley Forge National Historic Park

Unable to wrest Philadelphia from British control, George Washington led his army to Valley Forge, eighteen miles northwest of the city, to camp for the winter. From December 19, 1777, to June 19, 1778, the Continental Army trained under Baron Frederich von Steuben while struggling with the cold, lack of supplies, and disease. Between 1,700 and 2,000 soldiers died while at the camp. Today, the Valley Forge National Historical Park features 3,500 acres of monuments, meadows, and woodlands commemorating the sacrifices and perseverance of the Revolutionary War generation.

Independence Hall

Independence Hall is the birthplace of America. The Declaration of Independence and U.S. Constitution were both debated and signed inside this building. The legacy of the nation's founding documents - universal principles of freedom and democracy - has influenced lawmakers around the world and distinguished Independence Hall as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Fort Ticonderoga

Fort Ticonderoga, formerly Fort Carillon, is a large 18th-century star fort built by the French at a narrows near the south end of Lake Champlain, in northern New York, in the United States. The capture of Fort Ticonderoga was the first offensive victory for American forces in the Revolutionary War. It secured the strategic passageway north to Canada and netted the patriots an important cache of artillery.

Fighting on the side of the British was Mohawk leader and warrior, Thayendanegea, or Joseph Brant, whose volunteer unit was infamous for waging guerilla warfare tactics against the Patriots during the Revolutionary War. You can learn more about this brave warrior at the American Revolution Experience.

Mount Vernon

Mount Vernon acted as the former plantation estate of the legendary Revolutionary War general, George Washington. The current estate includes the original mansion, gardens, tombs, a working farm, a functioning distillery and gristmill, plus a museum and education center.