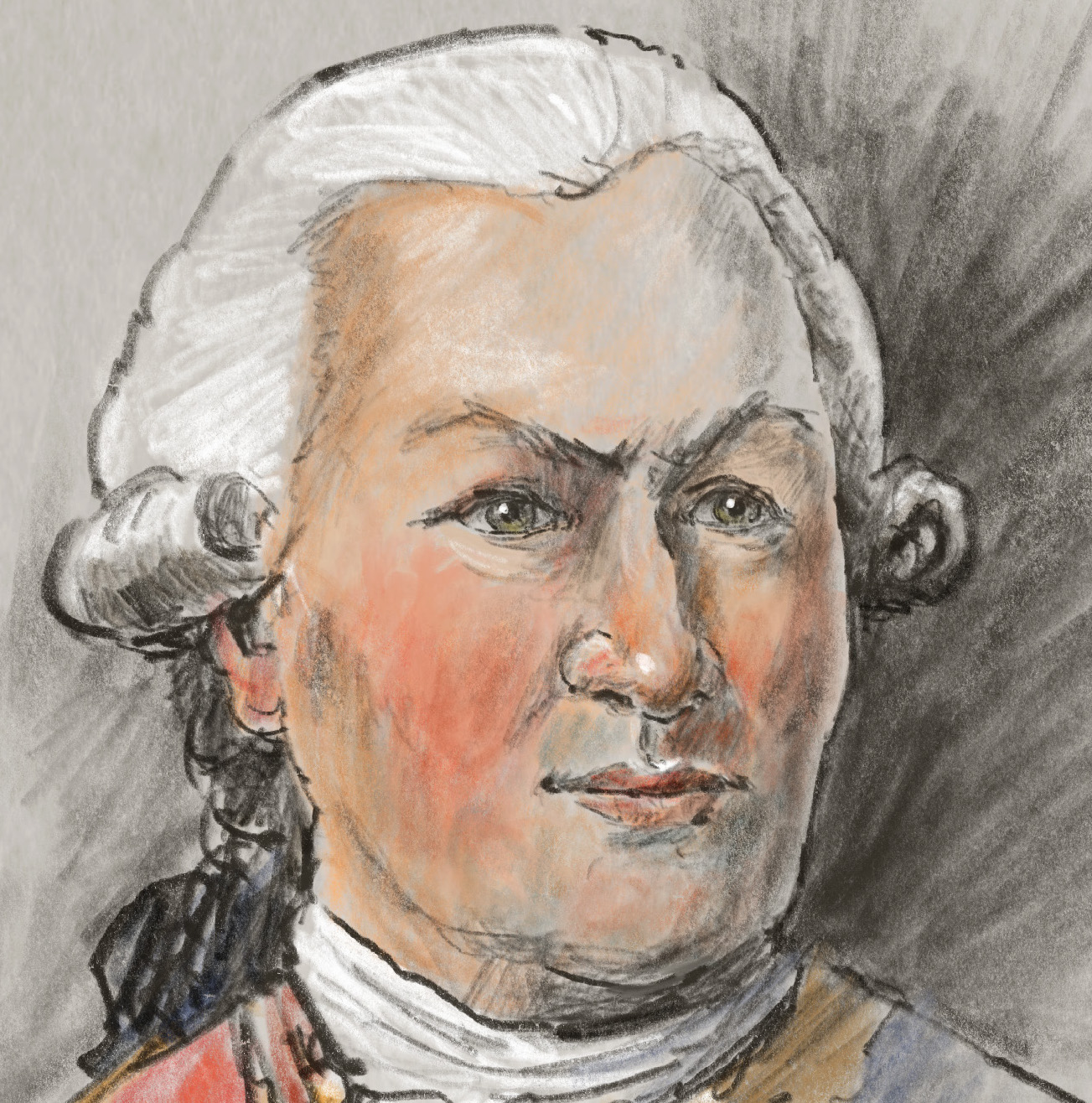

Winsor Fry

Former slave fighting as a patriot, and navigating life in a new nation

Like many soldiers of the Continental Army, Winsor found it difficult to make a living. As a free person of color, post-war life may have been especially challenging. Further, primary documents suggest that he was illiterate, making only his mark instead of signing his name. He applied for a military pension in 1818, and included in his paperwork the record card for a 100-acre land grant which he had never received. He applied again in 1820, describing himself as “much out of health & broken down with infirmities,” and received a pension worth around $8 per month. At the end of his life, he may have been physically unable to travel to Providence to collect his pension. The final amount, collected by the administrator of his estate after his death in February 1823, was the accumulated amount due to him from September 1822 to the end of his life.